Forage sampling and analysis is the most accurate way to test for forage quality. Knowing the nutritional content of the hay can be used to create a balanced ration which is a critical component of nutritional management for horses. The North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Farm Feed Testing Service provides producers with a detailed analysis that includes important nutritional components. A complete analysis costs $10.00. It is important to get a representative sample of the hay that will be fed in order to get an overall picture of the quality. There are different ways to sample hay. Click HERE to see an older NC Horse Blog post on sampling hay. When filling out the forage analysis submission form it is important to indicate what forage type and animal species the hay is intended to feed because there are different equations used for different species when determining some of the results.

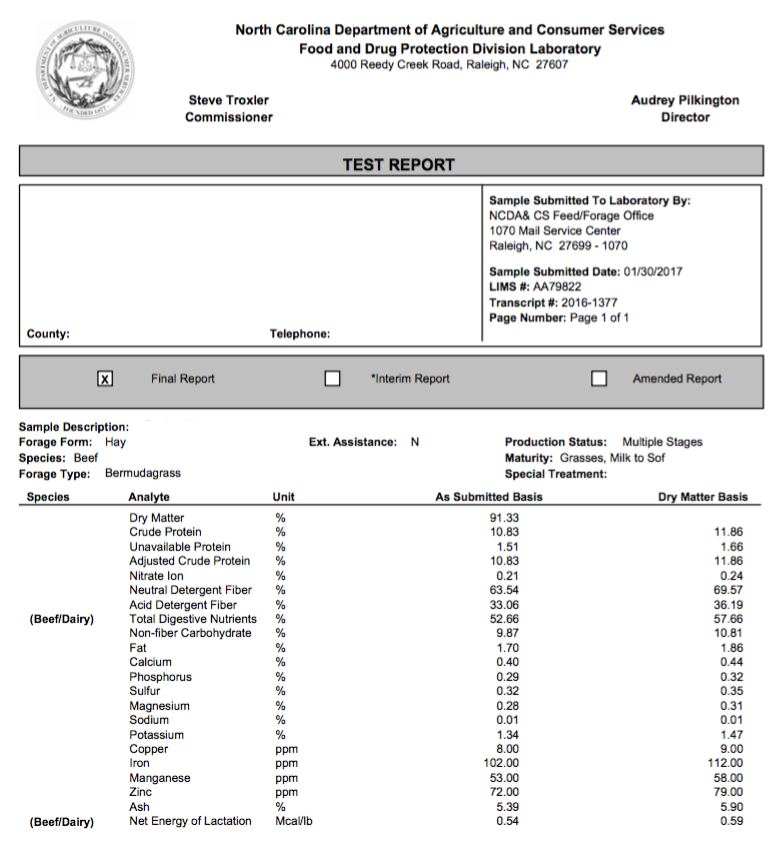

Above is an example of the results from a complete analysis. The analysis sheet has two columns of numbers, “As Submitted Basis” and “Dry Matter Basis.” All interpretation of the analysis is based on the column “Dry Matter Basis” because dry matter level (moisture level) varies in each sample and putting them on a dry matter basis makes the information easier to interpret. Listed below are the more important numbers to pay attention to when analyzing your forage results and determining your hay quality.

Dry Matter % The amount of dry matter in a feed is a key piece of information. The percent dry matter influences how stable dry forages, such as hay, will be in storage. Dry matter of hay should be at least 80% or the bales could possibly heat in storage which will result in damage to the nutritional value and they can grow mold. Another concern is spontaneous combustion. A dry matter of higher than 85% is preferable for hay for best results.

Net Energy (lactation), Mcal/lb and Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN) % Net energy and TDN are two measures of the energy content of the forage. TDN is used to help balance rations. The total energy needed will vary depending on the status of the horse. The more work a horse does, the higher its energy requirements. A mature horse at maintenance requires 57% TDN and a mature horse in moderate work (jumping, dressage, barrels) requires 60% TDN. Usually, the higher the TDN the better the hay quality.

Crude Protein %, Unavailable Protein %, and Adjusted Crude Protein % Crude protein (CP) is one of the key nutrients in feed. Any forage has a small portion of protein that is bound and unavailable to the animal and is called Unavailable Protein. If the unavailable protein exceeds 10% of the total crude protein it means that the hay was probably heated, resulting in some damage to the proteins. Any bound protein exceeding 10% of the total is subtracted resulting in the Adjusted Crude Protein. Adjusted Crude Protein is the value that should be used to evaluate the forage and balance rations. In most forages this will be the same as Crude Protein. Young, growing horses usually require the highest amount of protein. A mature horse at maintenance requires 8% CP and a mature horse in moderate work (jumping, dressage, barrels) require 10% CP. Different grass species will have higher CP, such as alfalfa, while others, like bermudagrass, will have lower CP. Orchardgrass and timothy are usually in the middle. Generally, the higher the CP the better the hay quality.

Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) % Acid detergent fiber is an indicator of the amount of energy in the forag and stage of maturity the grass was harvested. As the grass gets more mature, the less digestible it becomes. ADF is the less digestible fiber portion of the forage, so the higher the ADF level the lower the energy.

Calcium and Phosphorus % Calcium (Ca) and Phosphorus (P) are important macro nutrients (major minerals) that are rarely deficient in forages. Generally, forages are higher in Ca and lower in P, while grains are higher in P and lower in Ca. It is important that the ratio between Ca and P (Ca:P) is between 1:1 and 2:1.

Nitrate Ion % The nitrate ion detects the amount of nitrate in the forage. Too much nitrate can cause nitrate poisoning. Nitrate poisoning is a concern in ruminants but rarely affects horses. High nitrate levels can be caused by a number of conditions and is more common in some forages, such as sudan x sorghum hybrids. Please click HERE to learn more about nitrates and nitrate poisoning.

There are also results for Magnesium, Sodium, and Potassium % and Copper, Iron, Manganese, and Zinc ppm. These minerals are usually not a concern if the horse is getting grain. If a horse is just getting hay, then a mineral supplement may be needed.

Forage analysis, along with visual appraisal, can help you select the best hay for your horses. This article was intended to give a brief description of the items that appear on the forage analysis report to help you make an initial interpretation of your results. Contact your local Extension Agent for a more detailed interpretation and assistance with forage sampling and help with balancing your horse’s diet.